Abstract

Following the microservices architecture implies that each service has its own private data store, specific to its own needs (SQL DB, cache DB, document store, etc). This architecture has lots of benefits we won’t detail here. But it also creates new challenges.

How do you implement business transactions that are consistent between your services?

How do you query, access and join data across the different services without adding new pressure on the data stores?

How do you minimize services dependencies?

Microservices architecture problems

In a monolithic application, components invoke each other via its language function calls. On the other hand, a microservices architecture is a distributed system, running on different machines (potentially in different languages), which each service is communicating with each other via an Inter-Process Communication (IPC) mechanism.

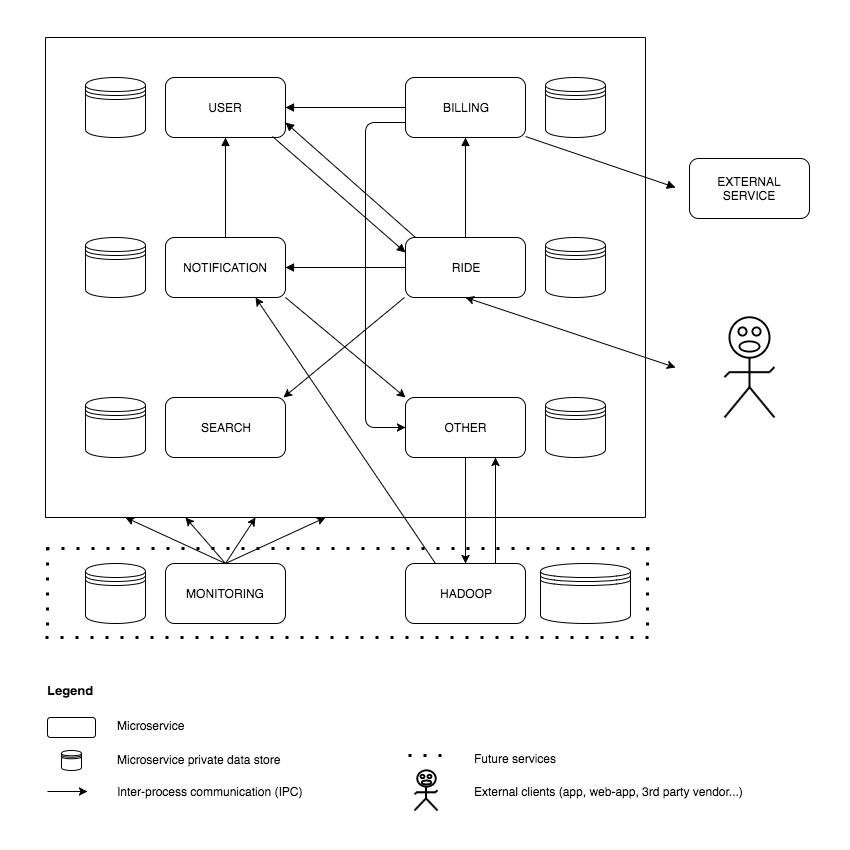

The schema above is a simplified representation of an Uber-like product, a common way of implementing a micro-service architecture.

You can note my special design skill

Each service aims to solve one business logic, has its own private data store and expose a few methods through an API.

Generally, the exposed APIs and services IPC are done through web services (usually REST HTTP Request / Response mechanism).

We can pretty easily see that, despite microservices architecture benefits, it adds lots of scalability issues:

- HTTP Request / Response is inherently a synchronous blocking mechanism

- Adding new services generates exponential dependencies between services and increases services & DB pressure

- A micro-service is as slow as the slowest micro-service in your call chain

- A service might be down because of failure, maintenance or overloaded and thus responding slowly to requests

- One slow micro-service can cascade up through the entire architecture

- Flows of requests that uses multiples services can be hard to model, implement and debug (specially in the case of concurrent requests)

- A client service must know the location of each (new) service instance

- …

The schema above is skipping lots of relations to keep it readable. But one can imagine the increasing complexity when adding new services, services communication between each other and the outer-world, etc.

An ideal micro-service is independent and can evolve on its own. This architecture naturally pushes us away from shared mutable states. To successfully implement a scalable micro-service architecture, we need to embrace it and communicate as much as reasonably possible in an asynchronous real-time manner.

Event-based micro-service architecture & data management

How can we decrease services dependencies, while adding an infinite number of new services, access their data from anywhere while keeping each service data store private and without adding pressure on it?

It seems like an impossible paradox to solve.

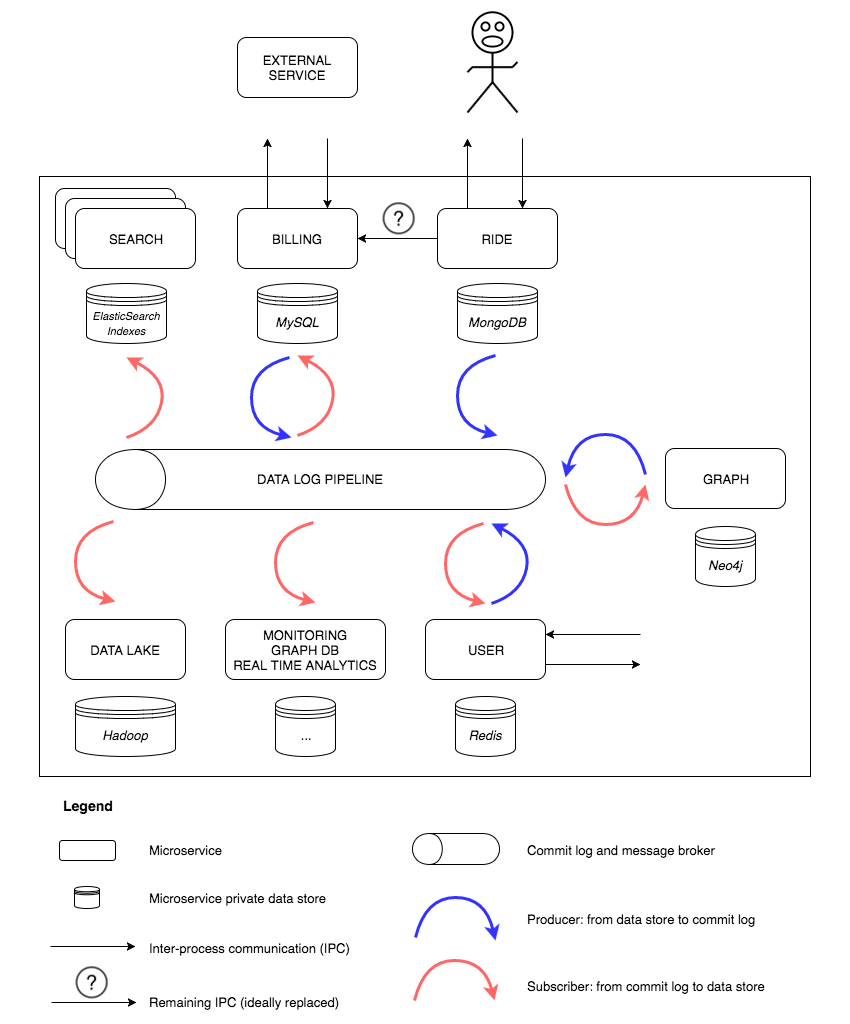

Except if you introduce a data log pipeline in your architecture.

The data log pipeline

A data log pipeline, also called streaming log pipeline, is basically an append only immutable commit log.

A commit log is an old simple concept used in almost every databases. It is called WAL log for PostgreSQL or binary log for MySQL. It basically registers every transaction (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE…) as a commit log and can assure the ACIDity of the transaction, and can replay it in case of failure. This exact same mechanism is also at the heart of most databases replication mechanism when you add new replicas or followers.

The “real data” is this commit log. Once the commit acknowledged, the DB will then transform this data into a particular view, specific to itself. PostgreSQL is storing and indexing data differently than MySQL, and in a complete different way for a NoSQL database. Nonetheless, the real data is the raw transaction log itself, and not the representation of it. This is a fundamental concept to understand, in order to follow the rest of this article.

This type of system is called streaming pipelines. The most known is Kafka, but there are a few others like DistributedLog, etc. We will try to be agnostic to the chosen technology for the rest of the article since what’s important is the concept of it and what it brings.

The streaming pipeline allows the ingestion of the different transactions or messages using publishers and subscribers to access it. Think of it as a pub/sub mechanism like a message broker system (ex: RabbitMQ, ZeroMQ, …) but using the commit log at its core. It stores the streams of data safely in a distributed replicated cluster, that you can process efficiently and in real time.

The Ride example

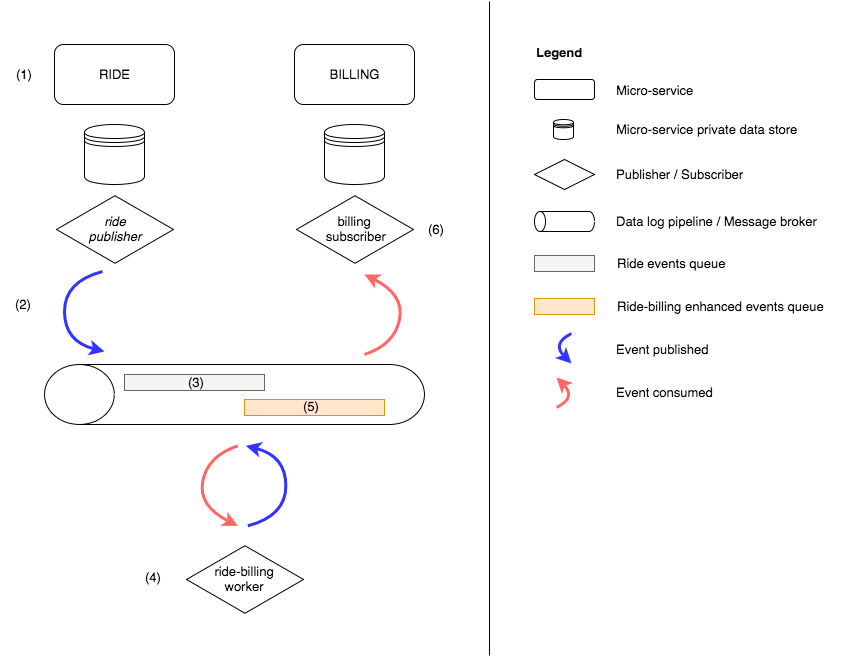

Let’s say the client in the first schema sends a REST request letting the system know that his ride is finished to the Ride Service. We then need to invoke the Billing Service, with some information like the length of the trip and the user.

With a REST interface, let’s say that the Ride Service would need to wait for a response from the Billing Service before responding to the client.

We see different problems here: Ride Service requires the Billing Service to be up and responding, and the Ride Service can’t respond to the client before the Billing Service does. This is a highly coupled pair of services. What happens when Billing Service performance degrades? What’s its peak performance? What happens when we release a new version of the API? Does the Billing Service itself is dependent on another external/internal service? …

Let’s see how it would work with the data pipeline and its persistent queues:

The Ride Service applies its business logic (1) and invoke a publisher which will basically send a message like { user_id: 42, ride_id: 54, ride_length: '42mn', status: 'ARRIVED' } to the message broker (2). The Ride Service can respond to the client as soon as its message is safely saved in a queue (3) and acknowledged. This system ensures us that the message will be processed at least once. So it will eventually make it to the Billing Service, as soon as Billing Service workers consume the message.

Note: the log or message can be in any format (text, JSON, or binary protocols for efficiency like Protobuf or Avro).

The Ride Service is now loosely coupled to the Billing Service and it is only dependent on the data pipeline uptime and performance, which is largely superior to the Billing Service. The Ride Service does not even need to know the Billing Service exists or how to use its API!

The Billing Service will probably need some extra information about the ride or the user. Some subscribers (4) can pull data from the pipeline different queues and join data to produce a new enhance commit log. This is called streaming processing (ex: Spark Streaming, Samza, …). For example, we could have a worker that will enhance the ride event, joining the user_id with data from the user queue of the system. It will then publish this joined data event to a new queue (5) which will be consumed by the Billing Service subscribers (6).

Once the Billing Service successfully processed the ride event, then it could emit its own billing event, and the Notification Service would catch it up and send a notification back to the user for example.

Reliability of the data pipeline

We can see on the schema above that this data log pipeline is a central piece that could potentially be a bottleneck or a single point of failure to the entire architecture.

Well, keep in mind that the “data log pipeline” block is schematic and it really depends on how the inner of this system works.

Obviously, to clear these concerns, the pipeline must have the following attributes: very high availability, scalability, concurrent, stateful, distributed & fault tolerant, high throughput and low latency.

Let’s take a more detailed look at these requirements:

- High availability: it must be up and responding all the time, without downtime

- High scalability: it must be infinitely extendable by adding new server nodes and disks

- Concurrent: it must accepts an infinite number of clients

- Stateful: it must provide “commit” semantics to the writer (i.e. acknowledging only when writes are guaranteed not to be lost)

- Distributed & fault tolerant: the cluster and its data must be replicable in case of failure

- High throughput & low latency: it must be able to ingest billions of events in a speedy manner

What are the benefits of using a distributed commit log?

This data log pipeline helps us with the concerns stated in the previous paragraphs.

1) Decoupled services

Each service would connect its own commit log by publishing events to the data log pipeline. Then, any service that needs access to some specific data would implement a worker subscribing to the wanted events and act on them.

This would decouple the services dependencies. They won’t require any new endpoint to be implemented to access / retrieve service specific data. The microservices are acting independently, working primary on their own business logic and they do not need to know the existence of the other services.

Since services are now really decoupled and they are not querying or waiting on another service to be implemented or to respond, it does not add any pressure on the service private data store or the service itself.

Synchronous accesses are replaced by an asynchronous mechanism, injecting and consuming data at their own rate. This is an ideal situation though. In reality, as we can see on the second schema, there are still some synchronous calls (ex: HTTP Requests / Responses from an external client). This situation is fine for external clients, but should be much avoided between services themselves. Instead, the service should publish an event of the action it just did and let subscribers listen and respond to it. If there is still a need for a direct synchronous call, then the way services have been split up into must be rethought.

Using this mechanism, unpredictable spike loads are absorbed by the queuing system, and all microservices stands up still.

You might wonder if this commit log collection process couldn’t add any new pressure to the data store. As stated earlier, this is the same mechanism used to replicate the master DB to n followers. It’s very efficient and does not impact the master since it’s the followers’ task to read the master commit log at their own pace.

This shift towards asynchronous access to data requires implementation changes and some business logic changes. But the implementation work is deported to the publishers and subscribers workers only, and does not impact the end service you are publishing to, but only the service you are working on.

3) Data stores stay private

Data stores are not anymore accessed directly by other microservices. However, data changes are populating the data log pipeline asynchronously, making data access for other services available for consumption.

For example, a new service like a search engine can be plugged to the data pipeline to index documents in its own data structure at its own pace. Moreover, this search service is not bind to a specific data store, but can index any data it needs.

Although other microservices could potentially publish an update event of a model it does not own, this is strongly not recommended. Following the Single Writer Principle, only the service in charge of a business model should alter the data.

The data pipeline also comes with some security features, to communicate with it securely and to manage ACLs on the different queues (who is authorized to read / write etc).

4) Extra benefits

Lastly, it makes raw data available to everyone. That means you can easily evolve your system by adding new services, but also new complete systems like a Hadoop data lake, a real-time monitoring engine, a second search engine to compare it with the current one, perform a seamless DB migration or put up a one time graph DB for analysis. Possibilities are endless here.

These situations arise all the time, as your company, product and team evolve over time. But usually, adding a new brick to your system is painful and slow, as your data is exploded into a wide range of inaccessible systems and formats. With this data pipeline, not only you have access to all the data immediately, you also don’t put extra pressure on existing systems at all.

One of the huge benefits of the commit log is that you can rewind and replay the states of your data since the beginning. You can add a new analytic system and still be able to analyze data from the past or through the window of time you desire.

You can also plug some real-time processing engine on it, ingesting and working on data as it arrives.

Conclusion

There are obviously some drawbacks to this solution. Adding this data log pipeline is more complex than a monolithic app with ACID transactions. Also, there is a need to implement compensating transactions to recover from app-level failures, there could be temporary inconsistencies because some data are not consumed / updated yet, and subscribers must detect and ignore duplicate events.

Using a data log pipeline like Kafka makes decoupling of microservices a reality. The traffic is amortized with a queuing system. The microservices are really independent and can evolve on their own, while at the same time, sharing their data for any service (current or future) to use.